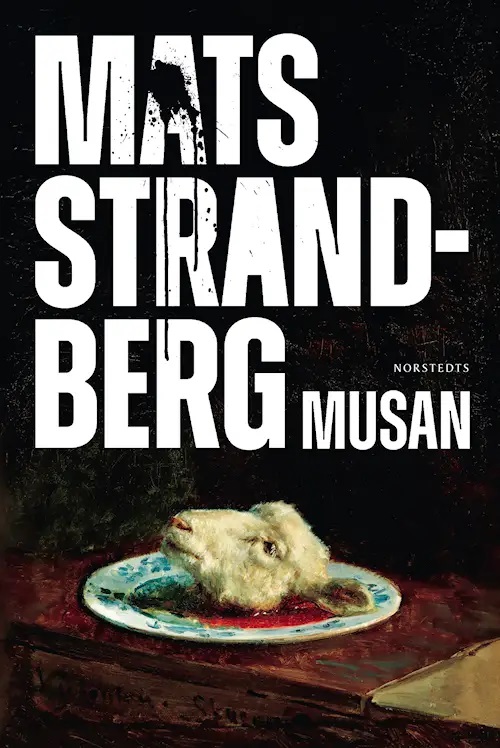

With my colleague Ian Giles, I was recently asked to translate a sample of The Muse, the new book by Mats Strandberg. It’s the story of Hedda, a struggling writer whose best idea – in fact, her whole life – was stolen by a college friend from whom she was once inseparable. Specifically, it’s the story of what happens one hot summer when she reconnects with that former confidant and ends up staying at his parents’ country place – a weird, stifling manor house in the Swedish countryside.

Working on a translation is always a fun process, but this time Ian and I were genuinely struck by the creeping sense of dread and wrongness skillfully woven by the author as Hedda’s visit progresses.

The sample only covers the first 70 pages, so we had no idea whether this unsettling prelude laid the ground for something even more claustrophobic and sinister, or whether the rest of the book might be disappointing. But at the London Book Fair in March, we got to meet up with Lena Stjernström, the literary agent representing the title, where she revealed the rest of the story.

And it is fantastic.

As Lena enthusiastically outlined how Hedda’s situation becomes increasingly nightmarish, I for one squeed with a mixture of horror and delight. Picture The Wicker Man meets Rebecca with a good dash of The Haunting of Hill House. And the big reveal will truly make you shudder. It would make an amazing TV series.

Musan is published in Swedish on 15 May, and the rights have already been sold to Finland. Needless to say I’ve got all my fingers and toes crossed that an anglophone publisher buys it too so all of my British friends get to experience it too! In the meantime, you can read the sample below.

(Apologies for the lack of first-line indents: WordPress won’t let me.)

Needless to say, rights enquiries should be addressed to Lena Stjernström at Grand Agency.

‘Why were you worried about me?’ Mummy asks.

They’re sitting next to each other on the unfamiliar bed. The walls are made of upholstered fabric in fleshy pink. In the daytime it was quite nice, but now it feels like they’ve been eaten by a giant animal.

Hugo wants to tell her. But she doesn’t pause long enough for him to work out how.

‘Nothing’s going to happen to me,’ she says, pulling him closer and kissing him on the head.

He wishes he could believe her, but terrible things happen to mothers all the time. They die in car crashes and fires and wars, and they choke and fall and are murdered. Hugo knows that in films and books, the worst always happens just when the main characters aren’t expecting it. When they think everything’s going to turn out fine. Then they stand there, open-mouthed and sobbing, wondering how things could go so wrong.

Hugo could start crying now. His eyes are burning and there’s a lump in his throat making it difficult to swallow.

You have to be prepared. You have to expect the worst. That’s the only way you can be sure it won’t happen. That’s why he has to think about the parasite. How it will come and get them while they’re asleep.

‘You’ll see,’ Mummy says, nudging him. ‘I’ll get so old and so decrepit you’ll long to be rid of me.’

Hugo isn’t going to pretend to laugh. He hates that she’s trying to joke about it.

‘What are you thinking about?’ she asks.

There’s a parasite in this house.

When he looks up, he is dazzled by the bedside lamp. She wouldn’t believe him, but he knows he’s right. He feels it in his whole body. The walls are coming closer, as if the room is shrinking.

‘Nothing,’ he says.

He knows all about parasites. On YouTube, he saw a parasite that burrows its way in under the tongue of a fish. Then it eats the tongue until the tongue is no longer there. Only the parasite is left, in the middle of the fish’s mouth. The clip is playing inside his head now. Over and over again.

‘I was scared of the dark too, when I was a kid,’ Mummy says. ‘It’s really hard, but it’s a good thing too. It means you have an imagination.’

‘I don’t want an imagination,’ Hugo says.

There’s another type of parasite. A worm that people can get in their eyes. It eats them from the inside. They go blind and it hurts.

‘Imagination is the best thing ever. If you have a good imagination, you can never be bored.’

She smiles as she says it, as if it was something wonderful. But Hugo would rather be bored. He glances at the wardrobe door, which is also covered with the upholstered fabric. It stands ajar like an open wound, and a strange smell emanates from inside. Like a tea towel that needs changing.

She hugs him again. ‘Will you try to sleep now?’

‘Okay.’

He wriggles down from the bed and the air bed beside it creaks as he settles into position on his stomach. He tries to concentrate on the borrowed book, but the sentences are difficult and old-fashioned and he’s too conscious of the wardrobe.

The smell comes out of there in gusts. As if something was breathing in the darkness inside.

She looks there too. Their eyes meet for a moment, and she gives him an artificial smile.

Hugo knows the truth about the wardrobe now.

Mummy doesn’t like it either.

SEVENTY-FOUR DAYS TO MIDSUMMER

A non-writing writer is a monster courting insanity.

Franz Kafka

1.

The taste of burned coffee from the library staff room lingers in Hedda’s mouth. Between the shelves she gets a glimpse of the audience, which consists of three people in a sea of empty chairs.

‘It’s really strange that more people haven’t come,’ whispers the librarian.

She’s obviously worried Hedda will be upset. That’s why she’s told her about the newsletter, about the posters they displayed everywhere in the library, about the notice they put in the local newspaper, about the Facebook event. She wants Hedda to know they’ve done everything they could, but the librarian doesn’t understand that it just makes her feel even more of a failure. And also faintly guilty, as if she had cheated them when she accepted their invitation.

‘I’m sure it’s just the weather,’ Hedda says.

The librarian smiles in relief and glances at the black squares of the windows.

‘Yes, in this kind of downpour people just want to be at home.’

She knows as well as Hedda that they have now agreed on a story about the bad turnout – a story in which it is out of their control and thus no one’s fault.

‘But I’m sure the people who have come will find it very exciting,’ she continues. ‘It always makes for a more intimate conversation when it’s a smaller audience.’

Hedda smiles back and does her best imitation of someone who doesn’t want to run away. She strolls away along the row of bookshelves, pretending to inspect the books while someone announces through the speakers that the author event with Hedda Stromberg is about to begin. She arrives at a table of staff favourites and isn’t surprised to see Persephone lying there. It’s the latest edition, the one with the cover illustration of the young girl poised to bite into the pomegranate. The author’s name is twice as big as the title.

‘Do you know him?’ The librarian’s eager whisper makes Hedda cold inside. ‘I saw you were in the acknowledgements.’

Hedda turns around and looks at the librarian’s green dress with its pattern of owls and her round glasses with their thin gold frames. The expression behind the lenses leaves no doubt that the book on the table is her contribution. She looks exactly like Hedda would have done if she were fifteen years younger and worked in a library. And of course she loves David Ridings.

Hedda wants to say that David Ridings isn’t the person she thinks he is. Persephone isn’t the book she thinks it is.

‘It was a long time ago,’ she replies.

The librarian looks disappointed. She opens her mouth to speak when a demonstrative cough comes from the other side of the shelves. They both look at the clock on the wall. Two minutes past six.

Hedda’s nerves have suddenly disappeared. Anything’s better than talking about David Ridings.

They walk to the end of the bookshelves and she follows the librarian towards the small stage, where two armchairs await on either side of a table. Hedda’s first crime novel is propped there, its cover facing the audience.

‘Perhaps we don’t need microphones, what do you think?’ the librarian says, as they step out into the spotlight.

Hedda shakes her head, sinks into one of the chairs and takes a few sips of water. Then she smiles broadly at the faces watching them. Two are older women who return friendly smiles. The third, an old man with his arms crossed over his protruding stomach, smirks at her.

‘Is that meant to be you in that picture?’ he says, as if he has caught Hedda red-handed.

She turns to the screen hanging behind the stage.

The Hedda Strömberg who meets her gaze from the author’s portrait has been in make-up for more than an hour, professionally lit and posed, and instructed to hold her head at unnatural angles to create shadows in the right places. The shiny red curls are the only spot of colour in the blue-grey shades of the photograph. It’s a picture worthy of the new queen of crime fiction that the publishing company had hoped for. Her father had just been admitted to hospital, but in the portrait there’s no trace of the stress spots she had on her chin or the bags under her eyes. She doesn’t even have any pores. And there is hope in the frozen gaze. The Hedda Strömberg of the author’s portrait is satisfied with the book despite it all. She believes that it might have something to say.

The real Hedda Strömberg turns around in her armchair again and takes another sip of water. She suppresses the memories of her father’s last weeks in Ward 5. Of the end-of-life care he received. A never-ending succession of morphine doses and incontinence pad changes. Christmas lights shining warmly in the windows, reminding them of everything they were about to lose. Her father had been so proud of Hedda publishing a detective novel. ‘You’ll see that everything will be okay now,’ he said. ‘I just wish I’d been able to see it all.’

He must have been this guy’s age. Hedda looks at his shit-eating grin and wishes he was dead instead of her father.

‘Yes’, she replies. ‘It actually is me, believe it or not.’

Nobody smiles. The librarian asks for a round of applause for the evening’s author. When three pairs of hands stop clapping, she picks up Hedda’s book.

‘You’ve previously been famous for your young adult fiction, but this is the first time you’ve written a crime novel.’

Hedda smiles in embarrassment. She doubts that any of the people present know who she is.

‘Famous might be a bit much. But yes, I wanted to try something new.’

The librarian turns to the audience.

‘This is A Time to Kill, the first part of what will be a trilogy about police cadet Nina Ljung. Her mother is a retired priest, who is increasingly losing touch with reality through conspiracy theories on social media.’ She looks warmly at Hedda. ‘I think you describe their relationship so well. As a reader, you really feel Nina’s sadness and frustration.’

Hedda thanks her, and out of the corner of her eye notices the old man shifting impatiently in his seat. She wonders why he came, what he’s getting out of it. She recognises the type. They usually turn up with their wives and make out that they’ve come under protest. But he’s here on his own.

‘When Nina literally stumbles across her first murder victim, her mother’s knowledge of the Bible comes into its own,’ the librarian continues. ‘The brutal act also provokes reflections on the nature of good and evil.’

The last sentence is taken directly from the back cover text. The librarian pauses theatrically while she sets the book back in its place. Hedda looks reluctantly at the cover, with its ominous church tower beneath stormy skies, the back of the blonde woman supposed to be Nina Ljung.

It was a representative from the big publishing company who had contacted Hedda to say he liked her YA books. He wondered if she had ever thought about writing a crime novel. She hadn’t, not seriously. But she was flattered by the question and couldn’t stop thinking about it. In the end she sent him a pitch. It took months to get an answer, and the lengthy wait awoke self-doubt that made her question whether this was something she really wanted. Her constant need for affirmation prompted her to rush into the trap of her own free will. When she was offered a contract for a whole trilogy, she said yes without even thinking it over. The advance made it easy to close her eyes to her last remaining doubts. It was several times higher than the ones she had received for her YA books.

A Time to Kill was released in late January. The publishing company had bought good spaces on the front tables in the big chain stores, just inside the entrance. In the first few weeks she was tagged several times a day by book accounts on Instagram that had received a copy. She got a nice mention in one of the nationals – even if it was in a mass grave with other crime novels that didn’t deserve real reviews. And an average rating of 4 across the online bookstores and streaming services. But when she logged in to the publishing house’s statistics page, she could see that sales were stuck at just over 1500 copies. Well below the optimistic levels the advance had been based on. She was still hoping the book would take off, if only people liked it and talked about it to their acquaintances. Then in February along came the annual clearance sale and swept everything else away, and in March the real queens of crime began to release their books. They reigned comfortably at the top of the charts while Hedda’s novel was forgotten by the world. It was only then that she realised how much she had actually allowed herself to hope.

‘It’s a shame it isn’t going better,’ her publisher had said when they last spoke on the telephone. ‘The next book might take off, and then people will buy the first one too. But there mustn’t be more than a year between them.’

It didn’t sound like he believed it himself. Hedda Strömberg was his embarrassing mistake.

‘How did you get the idea?’ the librarian asks.

One of the old women cups her hand around her ear to hear better.

‘That’s always so hard to answer.’ Hedda clears her throat. ‘But I’m really just trying to write the books I’d like to read myself.’

The glare from the spotlights gets warmer. She considers taking off her far too tidy jacket, the one that makes her feel like she’s in disguise.

‘We’ll come back to A Time to Kill, but first I want to talk about you for a while.’

The librarian smiles in encouragement, and opens a black notebook that exudes her own dreams of becoming an author. Neat rows of ballpoint print, with a little star at the start of each question. A few of her colleagues come over and sit in the audience. One of them holds up his phone. Hedda smiles straight at the lens, aware that she can’t compete with the retouched image behind her. All she can do is try to look pleasant.

‘How did you become an author?’

Hedda pretends to think, as if she’s never been asked the question before.

‘I love books. That was how it all started. We lived way out in the countryside, and there were no other children nearby. So I read a lot instead, and used my imagination.’

It sounds like she’s poking fun at herself. The old women and the librarians look kindly at her.

‘Sometimes when I write it feels like I’m still making up imaginary friends,’ she adds, and manages to sound spontaneous.

There is polite laughter. But the man doesn’t crack a smile as he holds up his hand.

‘We’ll open the floor for questions at the end of the session,’ the librarian says.

But he can’t be deterred. And Hedda smiles courteously as she listens to his lengthy explanation about a Fiat that appears in the book’s flashbacks, even though that particular model didn’t actually exist in 1989. Hedda realises this is why the old bastard has come. Her mistake has given his life meaning. The two old women don’t react, but the librarian glances at her in pained understanding. Hedda crosses her legs and looks down at her oxblood-coloured boots. She smiles and smiles, thinking that David Ridings would never have made such a mistake in his books, but that if he had, the publisher or editor would have discovered it. They’re careful about fact-checking when they work with an important author. And if David Ridings had been sitting on this stage, the queue would have been right out into the street.

An hour later, she drags the wheelie case full of unsold books back to the hotel. Gravel and wet snow clog the wheels, making them stick. The town is depressingly familiar, even though she’s never been here before. The same square, the same shops as always. It’s stopped raining, and the sparse street lights are reflected in the puddles. Beyond the light cast by the street lamps, the April darkness is so compact that it feels like blindness.

She answered questions about strong women and where she finds her inspiration. About her writing routine. About whether she knew from the outset who the killer was, and how much Nina Ljung is based on herself. She gave helpful advice to everyone with dreams of becoming an author, and chatted to the other librarians afterwards and agreed that yes, it was a shame that there weren’t more people but you never knew with this kind of event. She posed with them for a photograph and uploaded it to Instagram, and wrote Thanks to everyone who came tonight, ♥♥♥ #Author #AuthorLife #ATimetoKill.

The tote bag with classic illustrations from Alice in Wonderland has slipped down her shoulder, and she pulls it up. She glares bitterly at a middle-aged couple who have just come around the corner, laughing at the sudden wind. She hates them for not having gone to the library. What else is there to do in this shithole of a town?

Get a hold of yourself, Hedda. You’re losing your grip.

You should check into your room, get something to eat in the restaurant, maybe even have a glass of wine to calm down. Then there’s still a few hours of the evening left. It will feel better if you write for a while. Just for an hour.

Even as she makes the plan she knows it’s a lie.

She’s supposed to deliver the first version of A Time for Silence, the next part of the trilogy about Nina Ljung, in early August. And the sales text for the publishing company’s spring catalogue should be ready then too. She’s told her publisher that things are moving forwards, that it feels promising, but in fact she’s only managed to produce a few thousand words – and she hates them all. They are flat and lifeless, already used. She’s written them all before.

Her wheelie case sticks again. She kicks one wheel hard, but it doesn’t help. The case bounces over the tarmac as she strides on between the puddles.

Stop feeling fucking sorry for yourself.

Fifteen years ago, you’d have loved to have these problems. Writing books was the only thing you dreamed about. And now you get to do it.

At least for a while longer.

The last thought makes her dizzy with dread. It’s a fear that Hedda recognises all too well, and she wishes it could give her a much-needed kick in the backside. But it’s not the sort of fear that gives her an energy boost. Instead it just hurtles around in her body, paralysing her completely. The advance that sounded so substantial is almost nothing if she divides it up into working hours. The money she got for A Time to Kill has already run out, even though she extended it with lectureship and translations and extra shifts at the old people’s home where her mother works. So what will she do if she doesn’t write the rest of the trilogy? How on earth will she support herself and Hugo?

The pedestrianised street ends in a poorly lit park that she didn’t come through on the way to the library. Last year’s leaves cover the ground, sodden and half decayed. The wind ruffles her hair when she turns around. There’s no sign of the middle-aged couple. Only dark windows and closed doors. An empty crisp packet flutters along the ground.

Hedda puts up the hood of her coat and takes her phone out of her bag, opening the map app. She enters the name of the hotel and lets the satellites floating silently through space stake out her path. But the map suddenly disappears. A familiar face fills the screen, together with his name.

David Ridings.

He’s standing on the stone steps up to Skillinge College, recently woken up and squinting in the spring sunshine with a cigarette in his mouth. Her own shadow lies folded over the steps.

It’s many phones since she last saw this picture, but she has never been able to bring herself to delete him from her contacts.

The connections in her brain misfire. Understanding arrives a bit at a time, with long delays in between. Her phone is still set to silent after the author event. The image hasn’t just appeared on her screen through some weird bug. He’s actually ringing her.

Do you know David Ridings? I saw you were in the acknowledgements.

She feels like she’s been found out, as if he knew she’d been thinking about him. On the other hand, she often thinks of David.

For a moment, she wonders if the librarian’s colleague posted his photo on Instagram, if David had seen all the empty chairs in front of the stage. But David doesn’t do social media. He doesn’t need to.

Hedda can imagine exactly what he’d say about the situation she’s got herself into. Authors often talk about their inner critic, but hers speaks with David Riding’s voice. Well-formulated and categorical. Always so sure of itself. It’s been a long time since she broke contact, but she’ll never be free of him.

Hedda stares at the picture. Not even his facial features show any hesitation. Thick, dark eyebrows. A strong nose. A well-defined Cupid’s bow. She’d forgotten how handsome he was back then.

She doesn’t want to talk to him, but it would be worse to go around wondering what he wanted. Before she has consciously made a decision, she taps the screen, then watches the seconds of the conversation begin to tick off. One. Two. Three. Far too fast, and yet so much slower than the beating of her heart.

Hedda puts the phone to her ear. There’s a crackle of static and she tries to turn away from the wind.

‘Hello?’ she says.

‘Is now a good time?’ David asks. ‘It sounds like you’re out.’

Over the years, Hedda has seen him interviewed on TV, heard his voice on the car radio on the way to Hugo’s preschool and hastily changed stations.

Hearing his voice again on the phone is something else entirely.

He sounds familiar and unfamiliar at the same time; there’s a nervous undertone in his voice that she doesn’t recognise at all.

David offers his belated condolences and says that he would have rung sooner if he had known. Hedda manages to stay on an even keel – right up until she hears him light a cigarette.

The sound plunges her back in time, to phone calls that stretched far past midnight. It’s like a Pavlovian bell. Hedda finds herself craving a cigarette for the first time since she was pregnant with Hugo.

‘Was that all?’ she says.

The wind makes the connection crackle again, but David remains silent.

‘Do you think we could meet?’ he says finally. ‘It would be easier face to face.’

‘I’m not sure’, she says quickly. But she’s already remembering that she’s due in Stockholm soon for her publisher’s spring party. ‘What is it you want to talk about?’

‘I want to say I’m sorry,’ David Ridings replies.

SEVEN DAYS TO MIDSUMMER

‘I believe every artist had someone who told them they weren’t worth dirt and someone who told them they were the second coming of the baby Jesus and they believed them both. And that’s the fuel that starts the fire.’

Bruce Springsteen

2.

The underarms of her bulky men’s shirt smell of wet cotton, and the prickly upholstery of the seat is itchy on the back of her thighs. She doesn’t even want to think about the sweat stains she probably has on her khaki shorts. It took an unreasonably long time to choose them this morning. She yanked clothes out of the wardrobe and rejected them as quickly as if she was in a montage from a 1980s film.

The bus from Kungälv was late, so she had to run to catch the train in Gothenburg. The modern commuter train from Västerås is the last leg of the journey that has taken Hedda half the day. The windows don’t open and she feels like she’s been steamed. Unfamiliar place names scroll across the digital display above the doors. The next stop is Skarpudden. Seven minutes to go. The information doesn’t make her sweat any less.

The only other passenger is a bald man in a hoodie listening to a loud football match on his phone. The crowd roars and the treble makes Hedda turn around and give him a meaningful look. He doesn’t even notice. Of course he doesn’t. She adds a passive aggressive sigh before she turns around, thinking that she’s turning into her mother.

Six minutes to go.

She drank far too much white wine at the spring party, and the evening is a series of contextless fragments of memory. The publisher who immediately went on the defence when she told him about the mistake with the Fiat. The sales manager who held court at the buffet but avoided her eyes. The courtyard with its clearly defined groups of successful writers and forgotten poets, giving her the sensation of being back at high school. Of not belonging anywhere. The following day, she had wobbled, still hungover, into the restaurant that David had chosen for lunch. ‘Now I remember why I stopped drinking,’ he said with a laugh.

Because that’s what David had wanted to tell her. He had joined AA and had reached the ninth step. That was why he had called her. He was trying to make amends to anyone he had treated badly. ‘You’re top of that list,’ he said.

His facial features were softer, he had gained a little weight and had a touch of grey in his hair, but it suited him.

He had asked for forgiveness even before the seafood chowder was brought to the table. He said everything Hedda had long since stopped hoping to hear.

‘Without you, there would never have been a book. You were right. I stole everything from you.’

He had succeeded in convincing himself that he wasn’t doing anything wrong. David had been an alcoholic even back then. He drank to get over his low self-esteem, but even when he dared to write, he was too drunk to produce anything worth reading.

‘Not that it’s any excuse,’ he said.

It’s only now he’s sober that he realises what he actually did. Realises that, deep down inside he’s known that all along.

‘I knew you intended to write about it yourself. All of my successes are down to you.’

And Hedda was shocked at how easy it was to forgive. To finally hear him admit what he had done was enough to dissolve the anger she’s been carrying all these years. It was such a relief not to have to bear that burden any more.

They FaceTimed almost every day during the following weeks. She began to realise how much she had missed him, how much she missed the person she was with him.

‘Come and celebrate Midsummer with us at the country place,’ said David during one of their conversations. ‘It’s just the family, so there’s no stress. We can sit and write together again. It’ll be like old times.’

The football game has finally fallen silent. All she can hear is the gentle humming of the train. Outside the windows, the forest rolls past against a white sky. Now and then she gets glimpses of the lakes that are linked by the Strömsholm Canal. Hedda roots out the pack of tissues from her tote bag and dabs at her face and neck. She glances at the man, who is still absorbed by his phone. Undoing the shirt, she reaches her hand in under her vest top, hastily wiping beneath her breasts. She has only four minutes to stop sweating.

She dabs at her face again and takes a selfie where she’s thoughtfully looking out of the window, adding a filter that tones down the redness.

Taking a break from social media for a whole week! Going on a writing camp with a good friend, and then celebrating Midsummer. See you soon! ✿✿✿ #Author #AuthorLife #ATimetoKill #ATimeforSilence.

David has asked her not to reveal their plans. ‘We never usually have guests for the major holidays. Someone might get upset if they saw it.’She agreed without hesitation, deciding to take a complete break from social media. Everything to focus on her writing.

These few days will be her lifeline. The manuscript has turned into quicksand. She writes a line and immediately deletes it again. She pokes holes in all her ideas as soon as they come to her. She’s too stressed to write, but until she gets something written she can’t be calm. And so she just goes around in circles, as her deadline creeps closer and she constantly recalculates the number of pages she needs to write per day to stick to the schedule.

But far away from everyday life, perhaps there will be hope. When she goes home again, a few days after Midsummer, maybe she’ll have managed to breathe life into her dead characters and their barren dialogue. But the idea of a week with David’s family is making her nervous. She’s never been in their company for more than a few hours at a time. Now, for the first time, she’ll meet them in their natural environment – a world that’s far removed from hers. She’s afraid she will lose herself completely in it.

Next station Skarpudden, the pre-recorded voice informs her through the train’s speakers. Next station Skarpudden.

Hedda posts the photo and looks up from the screen just as the trees thin out and then disappear completely. A large lake glistens beyond fields and meadows, like spilled mercury in the white light. She pulls on her trainers, having to force her heat-swollen feet into them. Outside the window on the other side of the carriage, a residential area with leafy gardens climbs up a steep hillside, and she wonders which of the houses David’s grandmother and grandfather inhabit.

The train slows with screeching brakes and Hedda gets up, tugs at her shorts and lifts the tote bag onto her shoulder. She feels the man’s eyes as she lifts her wheelie case down from the shelf and heads for the doors. Through the windows she sees that they’re passing an old station building with flaking, dirty yellow wooden walls and boarded up windows.

The platform is empty. There’s no sign of David.

You can still change your mind

Hedda looks back at the seat she has just left. She sways as the train stops and the brakes abruptly fall silent.

There’s a loud beeping from the doors and then they open with a hiss. The light outside is dazzling, even though she can only sense the sun as a white disc in the hazy sky. She puts on her sunglasses, takes a firm grip of the handle of the wheelie case and climbs down from the train.

3.

The compact mass of clouds is like a lid over the sky that lets in no oxygen and releases no heat. The train doors close behind Hedda, and the heat from the asphalt is already penetrating the thin soles of her trainers.

David comes jogging along the platform in loud flip-flops and a faded T-shirt. He looks like he hasn’t slept properly for weeks. His face is swollen and unshaven, his eyelids so heavy that they completely change the shape of his eyes. But he lights up when he sees her, and her last doubts evaporate as he increases his pace.

We can sit and write together again. It’ll be like old times.

Hedda goes to meet him. She reflexively pulls the bag straps up her shoulder again to reassure herself that she hasn’t forgotten it on the train, which has just started to move off.

In the middle of the platform they give each other a hug in the shade of an awning.

‘I’m sweaty,’ she says, but David merely hugs her harder.

‘Doesn’t matter. I’m just glad you came.’

The skin of his arms is so hot that it burns through the fabric of her shirt. It’s a relief when he lets go and Hedda can tug at her vest top so it hangs loosely over her stomach again.

Away by the old station building, the barriers slowly rise again.

‘How long have you been out here?’ she asks, and David grins.

‘Long enough for anyone to become an alcoholic.’

At least he can joke about it. That should be a good sign.

‘Is it that bad?’ she asks.

‘Grandfather’s preparing an exhibition at Moderna. It’s a retrospective, but he’s presenting five new works. I’m sure you can imagine.’

Hedda nods as if she understands perfectly.

‘And something has happened.’ David pauses, seeming to regret his words as soon as they have left his mouth. ‘We can talk about it later.’

He gives her another smile, more strained this time.

The wheels on her case seem unnaturally loud in the silence left in the wake of the train. Even the birds are too hot to make a sound. Hedda looks up at the wooden houses on the steep slope, seeing nothing in the windows, which reflect the white sky.

‘I brought a bottle of wine for Olof and Leonita. Is that okay?’

‘Why wouldn’t it…?’ David stops in mid-sentence when he realises what she means. ‘Of course it’s okay.’

‘I don’t need to drink either. It makes no difference to me.’

‘Nor to me either. Seriously, Hedda. I just want you to enjoy this week.’

They’ve reached the end of the platform, and David halts her as she heads towards the houses on the hill.

‘We’re going this way.’

When she turns around, he’s already crossing the tracks on the other side of the platform. Beyond the raised barriers, a gravel road cuts through a flower-filled meadow, towards the shimmering white lake. And up on a wooded bluff, she glimpses red bricks and large windows between the tree trunks. The spire of a square tower extends to the sky like a raised weapon.

She comes to a complete halt. The house is enormous. A mansion from a novel by one of the Brontë sisters, or an Agatha Christie novel in which the owners complain about how death duties have risen after the Great War.

‘My god,’ she hears herself say.

So this is where David’s grandfather and grandmother live. This is the house he calls the country place.

She should have understood.

‘Mother and Father are already here,’ says David as they start walking along the gravel road. ‘Joakim and Ellie are arriving in a few days.’

She’s never met David’s older brother. She’s only seen Facebook photos of a guy with blond dreads and kauri shells around his neck – named after Joakim Thåström, just like David is named after Bowie. Back then, Jocke was backpacking in Asia or working as a diving instructor in Egypt. The sort of life that’s easy to live when there’s a trust fund waiting at home.

‘Ellie?’ she says. ‘Is that his new girlfriend?’

‘His daughter. She’s nearly eight.’

Hedda looks at him in surprise.

‘She’s almost the same age as Hugo, then.’

‘Did I never tell you Jocke had become a father? We found out just after I visited you at the flat.’

‘No. I don’t think you ever mentioned it.’

She wonders if David also realises that they’re skirting the edges of the minefield now. There was a lot he didn’t tell her after that week when he came to visit. She had been recently divorced and the rooms were still full of moving boxes. Hugo was only six months old.

It was after that week that David started writing Persephone. For the first time, he barely spoke about his writing. He never asked her to read any of it. He said he was trying to find a new voice, that the process was too fragile. And she suspected nothing.

‘Jocke has turned into the black sheep of the family.’

Hedda looks at him curiously, and David smiles as if he’s going to reveal a terrible secret.

‘He’s in venture capital these days. All he talks about are mergers and acquisitions.’

‘I’m already looking forward to it,’ she replies, and David laughs.

It must have rained recently, because the air is saturated with the scent of warm, damp soil. In the tall grass of the meadow, daisies and buttercups bend their heads. The buzzing of insect wings is constant and hypnotic. Before them, the road is blocked by a pair of iron gates, fastened with a thick chain. A lime-washed wall surrounds the whole bluff, to keep out unwanted guests. Hedda looks up at the house, which still only shows itself in glimpses between the crowns of the pines and the dense foliage of the birch trees.

‘How’s the writing going?’ said David.

‘Procrastination is part of the process, right? In that case, it’s going really well.’

He laughs again.

‘I’m meant to be submitting the first draft in August,’ she continues. ‘To be honest I’m not sure how I’m going to manage it.’

It’s the first time she’s said it aloud. She thought it would be a relief, but in fact it’s the opposite. It suddenly feels real. Irretrievable. Insurmountable.

‘But surely you can get an extension?’ says David. ‘Nobody will want you to publish a book that isn’t ready.’

He sounds so unconcerned. It’s easy for him to say. He can afford integrity. But Hedda has absolutely no idea what will happen if she doesn’t get the book finished on time.

‘We can help each other this week,’ he said. ‘I’m a bit stuck with my writing too.’

‘Is there anything we need to do to get ready for Midsummer?’ she asks to change the subject.

‘Don’t worry about it. My grandmother would rather do it all by herself.’

Hedda looks at the house again. It must be a full-time job to take care of, especially for an old woman like Leonita.

‘And she’s already fully stocked up,’ David adds.

She wonders if David will ask her to pay her share of the costs at the end of the week, and if it will be more than she can afford. He’s done similar things before. Hedda can’t ask. She doesn’t even know how. Instead, they talk about the tourist boats that ran along the canal when David was a child, and about the holiday village a few miles away where one of the worst mass murders in Swedish history took place just four years earlier.

The massive building rises majestically from the bluff. In an opening between the tops of the pines, she sees another tower – a brick cylinder lower than its square sibling – and thinks that Hugo would love it. The refrigerator door in her flat is covered with his drawings of knights and castles.

They reach the gate and David goes over to a mailbox made of sun-bleached red plastic. While he pulls out advertising brochures and window envelopes, she gets out her phone and aims it at the house.

The artificial shutter sound from the camera makes David look up with something like fear in his eyes.

‘I’m not going to upload it,’ Hedda says quickly. ‘I just wanted to show Hugo.’

David looks at her uncertainly before grinning with embarrassment and unlocking the padlock on the chain around the gates.

‘Sorry. I’ve been totally brainwashed by my grandfather. If it was up to him, he’d shut down the entire internet.’

‘Sometimes I wonder if that wouldn’t be a good idea,’ Hedda says.

The chain rattles loudly as David undoes it.

‘Last year, he asked Dad to call the Wikipedia editorial team and ask them to take down their page on the house.’

David laughs as he opens the gates, and Hedda gives him a weak smile. Of course, the house has a Wikipedia entry.

As strange as it may seem, it took a long time before she understood what kind of family David came from.

When she was twenty she arrived at Skillinge College with naive fantasies based on Brideshead Revisited. Life would finally start in earnest. She would finally find her tribe. And she would finally learn how to write.

At high school she was the only one who voluntarily read Karin Boye and Selma Lagerlöf. The one who had seen the most black-and-white films. The one who went to the theatre by herself to see Angels in America when nobody else wanted to come. She was as anorexic as her peers – it was the era of scrawny arms and concave chests on the red carpet – but Hedda stopped eating to imitate her literary role models. Both Joyce Carol Oates and Joan Didion seemed to be above all need for physical nutrition.

She was so black-clad and so old for her age. But at Skillinge her self-image collapsed. The whole of her identity. Hedda could no longer tell herself that she was different or interesting just because she had dreams of becoming an author. And the most influential students had a head start that she could never catch up. They had grown up with regular visits to the big theatres, were used to having museum curators and Swedish Academy members to dinner, had rubbed shoulders with writers and opera singers during the summer holidays on Gotland, or with leading authors and sculptors in Österlen. For them, the cultural world was completely demystified, neither idealised nor unattainable. They already spoke the same language as the teachers and could dismiss Hedda’s horror stories with statements like ‘It’s just too post-colonial, the political slant is too heavy-handed’. It was painfully clear that she had never read George Sand, even though in a desperate moment she claimed she had, and that she’d never heard of Benjamin Britten.She mixed up The Seagull and The Wild Duck during one discussion, and believed that Hamlet held up the skull during the “To be or not to be” monologue. On that occasion, Hedda received the same compassionate, embarrassed looks that she would herself have given someone who thought the monster was called Frankenstein. She had no opinions about broadsheet newspaper critics, knew nobody who wrote op-eds in the cultural press and had nothing to say during the discussion evenings about Proust organised by a skinny guy with a skinny scarf. But the others had plenty to say. They had so many thoughts, all the time, and never doubted that their voices were worth hearing. And that was true most of all of Vendela Torberg, the leader of the unmade-up girls with constantly sleep-tousled hair, the ones who talked about being born in the wrong time, the ones who longed for a past where art was appreciated for the sake of art, where beauty had its own value. It was their writing that was praised, against which everyone else’s was measured. With every lesson that passed, Hedda became more and more convinced that she was a fake who couldn’t understand the point of their impenetrable walls of text describing a state or trying to push the boundaries of language. She felt cheap and superficial in her longing for stories with action.

She had dreamed about Skillinge for so long, but she didn’t fit in there either. Not for the want of trying. She dug so deep inside herself that finally only an empty shell remained.

But in the middle of the autumn term, the guy with the dyed black hair and the Trust No Man necklace switched to her writing group, and everything changed.

‘I don’t think it feels like the author is rooted in this text,’ he said, and Hedda enjoyed finally seeing Vendela Torberg taken down a peg.

‘I think this section about incest feels like an afterthought.It’s obvious the author wants to shock the reader, but it’s just like a hollow special effect,’ he said. And Hedda loved him because he too could see that the Emperor was wearing nothing at all.

‘Here I think the subtext is more like a flashing neon sign’, he said, and they started smiling at each other in agreement.

David Ridings came from one of Stockholm’s most infamous suburbs, and yet he was respected by everyone. He never softened his criticism, he dissected their texts with a scalpel, and Hedda was amazed that it only made them admire him even more.

It was thanks to David that she began to trust her own instincts again, to be inspired by his boldness. He talked about becoming a writer in such a self-evident way. Without false modesty, without any thought of back-up plans.

They became inseparable during the autumn holidays, when only the two of them remained at the college. At that time, David had cut off contact with his family. He didn’t want to have anything to do with them, even going so far as to call them evil one night when they were drinking cheap red wine in his room. By the end of the holiday she had more or less moved in with him. For the first time, she was someone’s best friend. The person who came first. She finally felt seen. Chosen.

Was she in love? Perhaps. But it was a comforting love, because she knew it would never be returned. Like falling in love with a member of one of the boy bands they listened to – ironically, of course.

Naturally, she stopped going to the Proust nights. She didn’t need anyone but David. They cultivated their alienation at school, refusing to allow anyone into their two-person clique. It was them against the world. Hedda knew she was living in a cliché, and she loved it. At night they smoked and drank instant coffee until their bodies vibrated, and in the dawn they read each other’s work.

David never spared her. He could always put his finger on what didn’t work, and his praise meant all the more because she knew it was honest.

Meanwhile, she wasn’t so forthright. David’s writing often felt as polished and cold as shiny stones, but Hedda was the only one who knew how little self-esteem he had, how hard it was for him to write. If he was harsh in his criticism of others, he was even harder on himself. He was easily depressed, and Hedda knew it was genuine because he tried to conceal it. So instead she chose to encourage him, to emphasise the things she liked. She pretended it was a strategy to help David. In fact, it was more about the fear of losing him.

Of course she noticed people had stopped greeting her in the corridors, but she never wondered why they continued talking to David.

At the start of the spring term, he made Vendela Torberg cry in the writing group. It was the first time Hedda felt sorry for her. When she tried to get him to stop, Vendela directed her anger at Hedda instead.

‘David’s little puppy,’ she said. ‘You’re just trying to worm your way into his family.’

Hedda looked around the room in incomprehension. Nobody said anything. Everyone looked away from her. Including David.

‘You don’t know what it’s like to come from my family,’ he said afterwards in his room. ‘It was so nice that you didn’t know who they are.’

He had indeed grown up in the infamous suburb, until he started high school. But then his family had moved to Stocksund, a completely different kind of area. His father, Patrik Ridings, was unknown to Hedda but owned a video game studio valued at almost twenty million dollars. And David’s mother was Annika Svantesson, the director of Sweden’s national theatre and a prominent feminist. Several of her plays had been broadcast on SVT and were part of Hedda’s own cultural awakening. It was only then that she understood David’s self-confidence. Making himself an irritant never held any risk for him. He not only came from money, but also from a cultural capital that stretched back for many generations.

No wonder everyone listened to him. No wonder he had no back-up plans. The first jealousy had already begun to sprout in Hedda. A poisonous, invasive species that threatened to suffocate her.

And now it’s back.

The gates close behind them with a metallic rattling. She looks up at the house that’s just a house to David, while her only frames of reference are Gothic novels and Hugo’s fairy tale worlds.

She hears the chain rattling behind her. It was a mistake to come here. She’d forgotten what it felt like when the deepest roots of envy sucked all the power out of her body. How it made it unbearable to be David’s friend, even before Persephone.

His money, his security, his confidence and his self-evident place in the world. The flat his father paid for. His contacts in the top layers of the cultural sphere. All reminders of what she didn’t have.

Sometimes she felt like she hated her best friend. But she hated herself even more for her envy, for all the ugly feelings that could never be stated.

She mustn’t let it out again. Mustn’t let it ruin these few days.

‘Shall I take that?’

David doesn’t wait for an answer before he takes her wheelie case and walks ahead along the gravel road that carves its way up the bluff. Hedda takes a deep breath. Even the air feels different inside the walls. Fresher. A gentle breeze brings with it the cool smell of the lake.

‘Can we go swimming later?’ she asks.

‘We can swim exactly as much as you want,’ he replies over his shoulder.

She’s just about to follow when something catches her attention in the corner of her eye. Amongst the trees a sharp splinter of rock protrudes from the ground, as black as a rotten tooth. Small sculptures have been carved out of it and observe everyone who intends to go up to the house. Hedda hesitates for a moment before she leaves the road and follows a faint hint of path. Pine needles crackle under her trainers. Long strands of grass rub against her calves.

Reaching the stone, she counts nine figures. One of them is holding something resembling a harp. Another is carrying a ball on its shoulders. The bodies are roughly chiselled, with large breasts and hips. Their faces have been left unaltered by human hand and the rough stone transforms into a lazy smile here, a raised eyebrow there. She reaches out and touches one of the female figures. It’s surprisingly cold against her fingertips, and she thinks vaguely about underground rivers that have perhaps cooled the rock. When she takes a few steps to the side, the shadows shift over the women’s faces. The lazy smile becomes rapturous ecstasy. A condescending eye seems to glint beneath the raised eyebrow. The effect is both impressive and unpleasant.

‘Hedda? Where are you?’

She follows David’s voice with her eyes, but can’t see him. Further up the hill, the brush grows densely between the tree trunks, obscuring her view.

‘Coming!’ she cries, and hurries back to the gravel road.

David is waiting with her bag at the crest of the hill.

‘I was looking at the statues,’ she says, breathless.

‘They guard the house.’ David smiles broadly. ‘My grandfather’s father made them.’

He lifts her bag again and they enter the gravel-covered courtyard, where Hedda gets her first sight of the house in its full glory. As they head for the open entrance door, she tries to take in all the sharp angles of the brick façade, the steep black roof and the balconies with their forged iron railings. They pass a scruffy old Saab that looks out of place amongst all this beauty. In the flowerbeds, larkspur and gladioli shine like fireworks against the stone of the plinth.

‘I thought it would be nicer to stay here,’ David says.

Hedda looks curiously at him.

‘Where else would we stay?’

‘You’ll see.’

The contempt in his voice is impossible to miss.

An overgrown English dogwood is growing next to the steps up to the front door. The branches trail over the railing. In the damp heat, the scent of the flowers is stifling and heavy, almost animalistic.

She looks up and gets a sudden dizzying feeling that the house is leaning over her, about to fall and crush her. She reaches out and grabs the worn iron railing, but can’t take her eyes from the façade. The patterns formed by the bricks seem to billow.

‘Are you okay?’

Hedda blinks. The enchantment is broken and the house unmoving again. But the smell of the dogwood is still overwhelming. Her heart is beating at twice its normal speed, David looking at her in concern.

‘I probably just need a drink of water,’ she says.

David nods earnestly and disappears into the house. Hedda remains standing at the bottom of the steps, becoming gradually aware of the compact silence. She can’t even hear any buzzing of wings from the lavish flowerbeds. She squints tentatively up at the wall again. It’s still not moving

Nobody is visible in the windows. And yet she feels watched by someone with a bird’s eye view. Perhaps it’s the house itself.

She releases her rigid grip on the railing and goes resolutely up the steps and through the open door.

In the cloakroom, muddy Wellingtons and worn trainers are scattered about. Paper bags of recycling are lined up next to what appears to be a cellar door. Raincoats and fleece sweaters are carelessly hung on hooks, with scarves and hats entangled on the shelf above.

‘Grandfather?’ David’s voice comes from further into the house. ‘Grandmother?’

If anyone answers, she can’t hear them.

It’s a relief to get out of her hot trainers. In stockinged feet, she walks deeper into the house, finding herself in an enormous entrance hall where the ticking of a grandfather clock echoes between smooth, dark wood panels. A staircase winds dramatically towards a landing on the floor above, as if designed for a grand entrance before gathered guests.

Hedda’s wheelie case has been abandoned in front of an oil painting that takes up an entire wall – the only one not covered in wainscoting. There’s just a flat white surface, as if nothing should distract the viewer’s eyes from the painting. She’s never seen it before, but the artist is so famous that even Hedda can pick out his work without hesitation.

Axel Svantesson. David’s great-grandfather. The family’s first success story.

In the picture are a blond boy and a girl, their backs to Hedda. He’s pointing to something below the wrought iron balcony railing, but the painting doesn’t reveal what he’s looking at. In front of them is only a hazy green indication of treetops. The scene seems idyllic, and yet it awakens a deep melancholy within her. Is it because the boy’s slender neck resembles Hugo’s?

No. Something else. She searches with her eyes until she understands. The children are framed by the open balcony doors, which in turn are framed by a gleaming wooden floor and walls with patterned wallpaper. The composition is all straight lines and straight angles. But the children aren’t completely centred. They’re standing close to each other, as if they have left room for someone else, someone missing.

Hedda goes closer to the canvas and sees a bee stuck in the thick layers of paint. More than a hundred years after it was painted, she can still discern the brittle wings.

‘Here.’

David’s voice makes her jump. When she turns around he hands her a glass of water, and she drinks thirstily. It’s so cold that it hurts her throat, but her thoughts are finally clear.

‘Do you feel better now?’

She nods and wipes her chin, suddenly embarrassed by his probing gaze. And now she sees that her socks have left sweaty footprints on the herringbone parquet.

They go up the curved stairs, each step creaking beneath their feet. She lets her hand glide along the banister rail, and when they reach the upper floor her fingers are covered with grains of dust stuck to her damp skin. A pair of double doors is standing open onto a salon bathed in the white light from the windows. Beyond, she can see the glittering lake and the forest climbing up the mountains on the other side.

‘There’s a shower and bathtub there,’ David says, pointing to a closed door. ‘And a toilet of course, but you can only pee in there. For anything else you need to go downstairs, otherwise the pipes get blocked.’

This information makes Hedda no less nervous about the nine days before her.

‘Here’s my room,’ David continues, opening a door to the left of the stairs.

When she looks in, she recognises it immediately. The balcony doors are open today too. The wallpaper is still the same, and now she sees that the pattern consists of snowdrops against a dark green background.

David’s room is part of art history. As depicted by the great Axel Svantesson.

She walks through the door and looks around. A pair of oil paintings hang above the unmade bed, a couple of jumpers are thrown over a gilded armchair, and in front of the window stands a desk with a worn oak top. There are heaps of old games on top of the bookshelf. Trivial Pursuit, Scrabble, Taboo. Hedda looks at the worn corners of the boxes and tries to imagine David as a child, how he would nag the adults to play with him. But it’s impossible. Her eyes run across the spines of the books. Most of the editions are so old that they must have been inherited from previous generations of the Svantesson family. The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes. The Children of the Frostmoor. Oliver Twist. Ivanhoe. When she turns around, David is standing in the doorway.

‘Come on,’ he says. ‘Your room is upstairs.’

Hedda follows him into a walk-through room lined with wardrobes and linen cabinets, with dust bunnies along the skirting board. He points to a closed door at the other end, telling her that it is his grandmother and grandfather’s bedroom, before turning to the right and opening a door set with diamonds of leaded glass. It opens onto a claustrophobically narrow staircase, with a faint shimmer of pink light from the floor above.

Her case bangs against the walls as David carries it up. A heart-shaped spot of sweat has appeared on his T-shirt between his shoulder blades.

‘As you might expect, there’s no Wi-Fi in the house,’ he says.

She checks her phone as she follows him.

‘It’s fine,’ she says. ‘I’ve got a full 5G signal.’

When she looks up again she meets David’s expectant eyes. And then she sees the room that he’s calling hers.

The walls are covered in padded fabric in a powder pink shade, which seems to colour the very air itself. Fabric-covered buttons form a regular pattern. Through an open door, a Juliet balcony offers a view of the lake. On the other side of the room is a double bed. The window above the head end is also open, so that a slight cross-draught fans Hedda’s hot face. She looks out over the treetops, seeing the train station and the houses beyond it, the railway tracks disappearing into the forest in both directions. And she realises that they are at the highest point of the house on the bluff, at the top of the square tower.

‘King of the castle,’ she mutters, crossing the cream carpet and touching the wall above a neat, white-painted bureau.

The fabric feels rough against her fingertips, the padding firmer than she expected.

‘I hope you like it,’ David says. ‘Even if it’s a bit like a padded cell in a Barbie dream house.’

They grin at each other, but Hedda’s smile becomes forced when she catches sight of herself in a wooden-framed mirror leaning against the wall. The glass has no filters that can magic away the bright red patches on her neck, no strategic cropping that leaves her cellulite outside the frame. Her body looks heavy and palpably physical in the light, girlish room.

‘I feel extremely un-Barbie just now,’ she says, opening a door covered in the same upholstered fabric.

Behind it, she finds a long narrow wardrobe that extends behind the wall. A faint scent of mould oozes from the darkness. Once upon a time the wallpaper must have been white, with clusters of roses, but it’s now bright yellow. Some of the rose petals are brown, as if they’ve withered on the wall.

‘Unfortunately there’s no toilet up here,’ David says.

‘I’m sure I’ll survive.’ She closes the wardrobe door and turns to face him. ‘I love it.’

David looks relieved, as if he had been truly worried, and suddenly she’s overwhelmed by a great feeling of tenderness for him. For their shared history. For how it was ؘ– before Persephone destroyed everything.

She walks over to a framed pencil sketch hanging above the bed, suspended from the picture rail with fishing line. A serious woman is posed rigidly, her hands clasped in front of her stomach. Judging by her dress, it was drawn a long time ago. Her hair is up in a tight knot, her eyes sorrowful.

‘Who is she?’

‘That’s my grandmother, Brita,’ says a voice that isn’t David’s. ‘This was her room.’

4.

Olof Svantesson is clutching the banister rail, and supports himself on a crutch when he steps up into the room. David’s grandfather has lost weight since she last saw him. The skinny calves protruding from his worn denim shorts are covered with blue veins. The checked shirt is several sizes too large, and the merciless light from the windows reveals the broken blood vessels on his fleshy nose, the dark bags under his eyes. Hedda wonders if he is sick.

And something has happened. We can talk about it later.

But perhaps Olof Svantesson has just got older. He must be at least ninety by now.

‘This is a study for Carl Larsson’s portrait.’ Olof stands next to Hedda, and they look at the sketch together. ‘He was a good friend of the family. The finished painting is hanging in the National Museum in Stockholm now. Perhaps you’ve seen it?’

She shakes her head, surprised it was Carl Larsson who brought Olof’s grandmother to life in pencil. The images that Hedda associates with Larsson are as uninteresting as a lifestyle account on Instagram, with sumptuous Christmas buffets, leafy gardens and joyful children.

‘Of course this is something completely different from his sentimental idylls,’ Olof adds, as if he has read her thoughts. ‘It’s more like his earlier work.’

They regard it in silence for a moment.

‘She looks so sad.’

‘My grandmother had a difficult life,’ Olof replies simply.

Hedda waits for a continuation, but none comes, so she pulls out the wine bottle from the bag still hanging on her shoulder. She immediately regrets the gift ribbon that she curled and tied around the neck of the bottle. It looks cheap and out of place in a tower room with fabric-covered walls and an original sketch by Carl Larsson, a good friend of the family. But she proffers the bottle to the old man who will soon have a retrospective exhibition at Moderna Museet.

‘For you and Leonita.’

‘Thank you.’ Olof smiles enthusiastically and myopically inspects the label. ‘This will be a treat. We’re not very familiar with wines from the New World.’

David throws himself down on the bed, and Hedda rummages in the tote bag again. Her fingers find the copy of A Time to Kill she has brought with her. But she hesitates. It’s hard to imagine Olof Svantesson reading a crime novel.

‘We’re so happy that you want to celebrate Midsummer with us,’ he says. ‘We’re in need of new blood here at Villa Thamyris.’

‘Thamyris?’

She tastes the unfamiliar word on her tongue, and Olof squints at her.

‘You don’t know him?’

‘Should I?’

His smile broadens. For a moment, she can sense a younger version of Olof Svantesson behind the aged face, and realises that he was probably handsome once. And if not handsome in the classic sense, then at least accustomed to making people like him.

‘It depends on how interested you are in Greek mythology,’ he says.

She glances quickly at David. If she had known more about the myths, would she have understood earlier what he was doing?

No. She would never have believed David could do such a thing.

‘I’m afraid that’s a gap in my knowledge,’ she says. ‘One of many,’ she adds, with something approaching defiance. But Olof’s eyes brighten under the heavy forehead.

‘You must fill that if you’re going to call yourself a writer.’

Of course she knows that Olof is right. The ancient myths are the origin of Western storytelling. The wellspring. But she’s never tried seriously, just as she never learned to appreciate Shakespeare or classical music. The project seems overwhelming – and frankly not interesting enough when there are so many new things to learn.

‘But you do know the Muses?’ Olof asks.

She hesitates. The word muse is something she associates with extremely human women, beautiful but interchangeable, whose sole purpose is to inspire male genius. To give birth to them in their artistry.

‘Grandfather,’ says David and sits up on the bed. ‘Perhaps we should let Hedda unpack before you start with the lecture?’

Olof looks as if in surprise at his grandson, as if he had forgotten that David was there.

‘Oh yes, of course. You’ll be exhausted after travelling across the country in this heat. You must forgive an old man who has at last found a new audience for his blethering.’

Hedda laughs.

‘You can tell me later.’

She finally makes the decision, and pulls out A Time to Kill from her bag. Ollie looks down at the shiny cover.

‘Thanks, but I’ve already read it.’

He’s still smiling, but doesn’t say anything more. The silence stretches out like an elastic band between them. Hedda has already signed the book to him and Leonita, but she replaces it in her bag.

‘Did you work out who the murderer was?’

She sounds too cheerful, dangerously close to manic. And Olof waves the question away as if it was of no interest.

‘I liked the author you wrote about. It’s an exciting idea that she can use her skill with intrigue to help solve the case.’

It feels like a consolation prize. The crime writer Disa Toivonen, a childhood friend of police cadet Nina Ljung, is only a minor figure in A Time to Kill.

‘Was she perhaps an homage to Ariadne Oliver?’

Hedda nods. When she wrote the book, she was afraid that the reference to Agatha Christie’s alter ego was overstated, but Olof is the first to make the connection.

‘You really have an eye for the human condition.’ Olof’s tone is softer now. ‘All murder stories are essentially tragedies. A life has been snuffed out. It’s unusual for a writer to make use of this aspect. You should really be commended for that.’

‘But?’

Hedda regrets it as soon as the short word leaves her lips, conscious that David is observing them. The carpet has become incredibly hot under her bare feet. A drop of sweat runs down the small of her back and trickles between her buttocks.

‘It didn’t seem like you were so interested in the police work,’ says Olof. ‘Those parts felt more like you were following a template.’

Those parts are the majority of Hedda’s book, and she smiles weakly.

‘Yes, but I’m writing in a genre. I was hoping I’d played enough with the conventions to make it feel fresh.’

Olof looks thoughtful. It’s clear that he neither agrees nor wants to lie. But he lights up when he catches sight of something behind Hedda’s back.

‘Look what we’ve got,’ he says, waving the wine bottle cheerfully.

David’s grandmother is on her way up the stairs with a light step.

‘Hedda,’ she says warmly. ‘Welcome.’

Leonita still has dark hair down to her shoulders. The same impossibly narrow neck, the same impossibly straight posture that can only belong to an aged ballerina. When they hug, Hedda can clearly feel her shoulder blades through the floral dress, but there is nothing fragile about the old body. The thin arms that hold her are strong and wiry.

‘I heard about your father,’ she says. ‘I’m truly sorry.’

‘Thank you.’

‘David says you were close to each other. It must have been difficult.’

Leonita’s consonants still retain a faint trace of the Balkans. She lets go of Hedda and looks at her with bright, black eyes.

‘This house is yours too, for as long as you’re here,’ she says. ‘We just want you to feel at home.’

Hedda can only nod, afraid her voice will betray her.

‘And we’re not exactly spoiled with David bringing girls here,’ Olof says, and laughs at his own joke.

Hedda glances at David, unsure of how she should react, but he merely rolls his eyes.

‘You don’t need to worry,’ says Olof. ‘I may be old but I’m not old-fashioned. My own father was homosexual. I’m just glad it skipped a couple of generations.’

He leans forward with both hands on his crutch.

‘The only thing I can’t stand is people of either sex who are bitchy.’

‘That’s enough,’ Leonita says.

But Olof continues to look at Hedda in amusement. A naughty little boy in the body of an old man. A little boy who has been caught out, but has no regrets.

5.

Once Hedda is alone in the room, she starts unpacking her bag. The bulky windbreaker is at the top, and in the all-pervading heat it’s hard to imagine that she will ever want to put it on. The hangers squeal loudly against the bar as she pulls them towards her. She’s just about to hang up her jacket when she gets the feeling that something’s wrong. Something at the end of the long narrow wardrobe, where the light from the windows barely reaches.

Hedda squints into the darkness until her eyes begin to get used to it. A vague discomfort causes the muscles to quiver across her back.

On the far wall, the wallpaper is lighter. It looks newer. Someone has tried to patch it so the clusters of roses line up, but they haven’t quite succeeded.

It’s not at all strange. And yet the skin on her neck is taut. She firmly hangs up her jacket, then continues with a long dress from Acne that was ruinously expensive even though it was second hand, and the back wall disappears from sight. When her case is empty, she rolls it into the wardrobe.

As she changes into a bikini, she glances at the tote bag with its illustrations from Alice in Wonderland. She can see the shape of her book, as if it were hiding behind the curtain that Alice lifts.

Thanks, but I’ve already read it.

Angrily, she pulls on a white sundress with black dots. Then she sits down on the bed with her phone and brings up the Wikipedia entry that disturbs Olof so much, the one about Villa Thamyris.

The photograph was taken from down by the lake. It’s winter, and the ice and snow highlight the steep cliff wall, making it as black as an inkblot on paper. From its elevated position, the house proudly shows itself off to the outside world. There’s a light on in the tower room where Hedda is right now, and she wonders who was here.

Down by the lake is a wooden house, which according to the caption was a coachman’s cottage. There’s a light on there, too.

Villa Thamyris, beautifully located by Lake Aspen, was completed in 1897, she reads. The façade is made of handmade brick, the roof of dark slate. There’s an enormous veranda on the side closest to the lake. She quickly skims through the section about the architect with a penchant for the neo-renaissance and instead focuses on Axel Svantesson, the house’s first patriarch. Olof’s grandfather seems to have begun his career as a highly mediocre painter on the fringes of the group that formed the Swedish Artists’ Union. It was during a visit to Paris that he met Brita, and they married just six months later. The move to Villa Thamyris changed everything, according to the quoted art historian. Axel Svantesson became a master at capturing the tiny details that make us reverent in the face of nature, and the intimate recognition in the everyday. His art was in phase with his natural romanticism and his quest to capture the Swedish idyll.

The page has a whole section about the famous people who visited the house, which is described as an important hub for the cultural life of the period. Both Carl Larsson and Anders Zorn regularly visited on their way to and from Dalarna. Parties and monthly visits are mentioned in the diaries and letters of luminaries like Verner von Heidenstam, Albert Engström, Gustaf Fröding and his sister Cecilia, Oscar Levertin, Ernest Thiel and his wife, Hjalmar Söderberg, Carl Milles, Tyra Kleen, Bruno Liljefors and Eugène Jansson. August Strindberg also visited towards the end of his life, before his and Axel Svantesson’s friendship came to an abrupt end after a quarrel over their life philosophies.

But there’s nothing else about Brita. The sad wife of the great artist doesn’t even get a red link.

Hedda has had enough for now. Instead, she enters Thamyris in the search box, and gets a short article about a singer mentioned in the Iliad. The son of Erato, the muse of lyric poetry.

But do you know the Muses?

She carries on. Wikipedia informs her that the Muses were goddesses in Greek mythology. Nine sisters who inspired artists and scientists and gave us words like museum and music. Hedda goes back to the short text about Thamyris. He challenged the nine sisters in a singing contest and lost. The Muses punished him for his arrogance.

Hedda searches the internet and finds more details about Thamyris. His eyes were gouged out and his tongue was cut off. He lost everything, including his mind.

And he wasn’t the only one. Others who challenged the Muses were flayed alive, or transformed into birds. Plato saw the Muses as a source of madness. They took possession of a sensitive soul and drove it to ecstasy and madness.

But the photographs of pottery shards, paintings and statues show an entirely different kind of creature. The nine sisters are depicted as beautiful, sweet female beings with neat little fingers, seductive glances and pale breasts under thin fabric. They want to please any artist who looks at them, not gouge out his eyes.

‘Are you ready?’

Hedda looks up from her phone. David is standing on the stairs, two bath towels in his arms.

‘I’ve just been reading about Thamyris,’ she says. ‘I understand even less now why the house is named after him.’

‘Remind grandfather to tell you tonight. He’ll love it.’ David comes up into the room and sits on the edge of the bed. ‘And ignore what he said. Your book is good.’

She looks gratefully at him and succeeds in not begging for more assurances. Do you really believe that? Is that really true?

‘It would have sold more if it hadn’t come out in January,’ he added. ‘Nobody buys books then.’

Her gratitude evaporates. She knows he doesn’t mean it, but David has reminded her both how big a failure she is and that she should have listened to her instincts. The publishing company’s plan was to release it in January to avoid competition.

David would never have let them persuade him. But she has to stop comparing herself to him. She won’t survive these few days if she doesn’t.

Hedda reaches for the bottle of sunscreen and squeezes some out into the palm of her hand.

‘It’s cloudy out,’ he says.

‘I’m good at burning myself anyway.’

‘I remember.’

She rubs it into her arms, and the greasy sunscreen mixes with the sweat on her skin, leaving white streaks over wide open pores.

‘What was the point of the song contest?’ she says. ‘What would Thamyris have won?’

David scratches at a mosquito bite on one knee.

‘According to some of the myths, he would be allowed to sleep with all nine sisters.’

‘His mother too?’ She rubs sunscreen over her calves, continues up her thighs. ‘It seems as if all my prejudices about Greek mythology are true.’

David gives a crooked smile, so she can see one of the sharp canine teeth in the corner of his mouth.

‘It’s only in some myths that he’s Erato’s son. The Muses are usually virgins.’

‘So virginity was the most precious thing you had, even if you were a goddess,’ she says, setting the sunscreen bottle on the bureau.

David’s smile becomes wider. Now it’s showing both canines.

‘You sound almost like my mother.’

‘Many people would take that as a compliment.’

He gets up from the bed, handing her one of the towels, with stripes in faded 1980s colours.

‘There’s a version in which Thamyris doesn’t challenge the Muses himself,’ he says. ‘In that one, it was Apollo who set the Muses onto him because he and Thamyris were in love with the same hero.’

‘Are there as many versions of all the myths?’ she asks, inhaling the scent of an unfamiliar detergent from the towel.

‘They were spread orally from the beginning. But they all end the same.’

Hedda lowers the bath towel and looks curiously at him.

‘People who compete against the gods always lose,’ he says.

6.

They walk through a dining room with burgundy wallpaper and dark wooden panelling. The room is still bright, thanks to the large windows facing the lake and the open door onto the veranda. The wall behind the scratched dining table has a hunting scene in intarsia. A woman on a horse aims her spear at a fleeing deer. When Hedda looks closer, she sees that the woman is pregnant. The beautifully carved foliage surrounding the scene extends up to the ceiling. They pass a fireplace so large that the mantelpiece is at Hedda’s eye level. A door stands ajar at the other end of the dining room, and she gets a glimpse of walls covered with bookshelves. It takes a moment before she understands why the lines of the bookshelves don’t seem to be quite right. The walls are rounded, belonging to the lower tower.

They come out on the veranda, which is bigger than her entire flat, and she thinks it must have cost a fortune to build Villa Thamyris. It’s no wonder Axel Svantesson managed to become a better artist here. The wide view of the lake is as beautiful as a painting, framed by decorative woodwork. Olof is sitting at a dining table with a coffee-stained waxed cloth, doing a crossword puzzle with a cigarette in his mouth. His crutch is leaning against the railing beside him. He looks up as he hears their footsteps on the soft wooden floor, and smiles when he sees their towels.

‘It’s probably warm in the water today,’ he says. ‘If I’d had the energy to get down the stairs, I would have jumped in too.’

‘You could take the car, though?’ says David, but Olof has already returned to his crossword.

They go down into the garden that extends right to the cliff edge, where she can see the wooden staircase Olof mentioned. The fresh green lawn is cool under Hedda’s bare feet. In the flower beds are aquilegias and peonies and foxgloves, and a wrought iron table and chairs stands in the shade of a silver birch. At the cliff edge, Hedda turns around and takes a look at the magnificent façade of Villa Thamyris. An important hub for the cultural life of the period.

The man who built the house on the bluff named it after an obscure figure from Greek mythology. And his grandson, Olof Svantesson, had an eager glance in his eyes when he asked if she knew the Muses.

David’s knowledge of antiquity is inherited in many ways. ‘That’s the only good thing I got from my family,’ he said at school, when he no longer wanted anything to do with them.In retrospect, it sounds like a delayed teenage revolt, just as dramatic and intense as anything else was for them back then. And David has come back to the family, to the house where he spent the summer and Christmas holidays as a child.